|

|

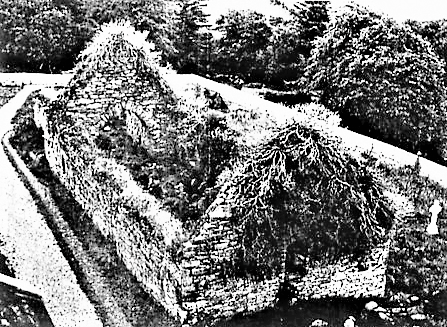

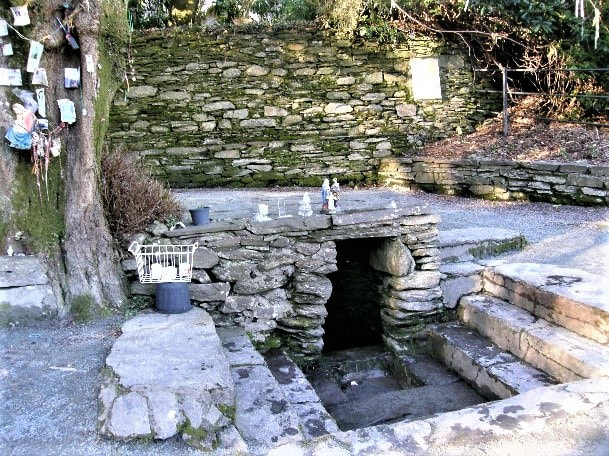

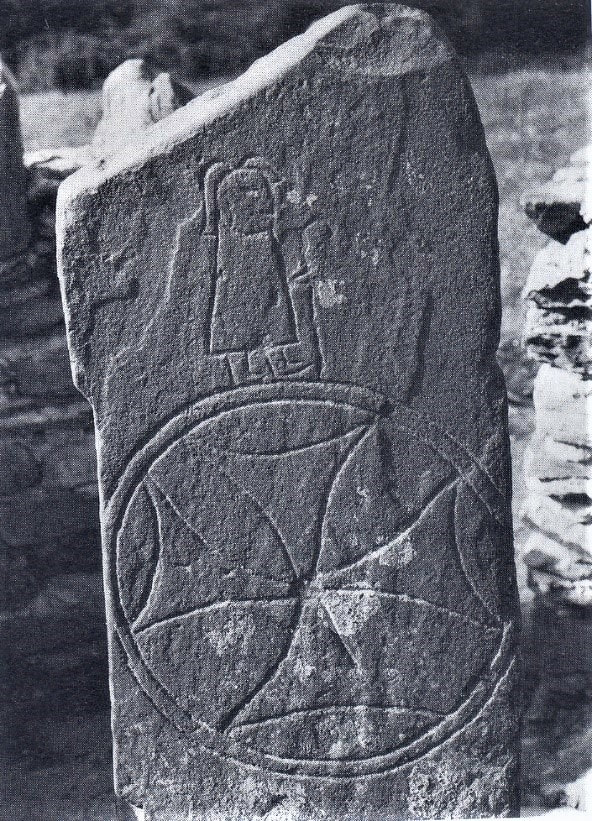

Tradition has it that St Gobnait founded a nunnery at the early church site at Ballyvourney, in West Muskerry, Co. Cork, in the 6th century. Although also linked with other churches and holy wells in Cork, Limerick, Kerry, Waterford and on Inisheer of the Aran Islands, this article will focus on the female saint’s cult at Ballyvourney. Her legend has survived mainly in oral tradition and while receiving little attention in medieval texts, it is interesting that an account of the life of St Abbán states that he blessed Boirneach (i.e. Ballyvourney) and gave it to Gobnait. Abbán is regarded as a secondary saint in the region, being overshadowed by the intense reverence to his female counterpart. By the post-medieval period, Ballyvourney had become an important centre for pilgrimage, and the annual 'rounds' called ‘Turas Ghobnatan’ were dedicated to the saint. The two annual pilgrimage ('pattern') days at Ballyvourney are the 11th February, which is St Gobnait’s feastday, and Whitsunday. The following will examine some of the surviving archaeological features traditionally linked with the saint and discuss the rituals associated with these monuments. St Gobnait's StatueJust across the road from the medieval church at Ballyvourney is a modern statue to the saint carved by the noted sculptor Séamus Murphy, and erected in 1951. Bees figure prominently on the statue given that Gobnait is the patron saint of beekeepers and is reputed to have sent a swarm of bees to rout cattle rustlers, who were attempting to steal cattle from the Ballyvourney people. Nowadays the pilgrimage round commences at the statue by making a request to St Gobnait with the following prayer: Go mbeannaí Dia dhuit, a Ghobnait Naofa, (May God bless you, O Holy Gobnait, / May Mary bless you and I bless you too, / To you I come complaining of my situation, / And asking you, for God’s sake, to grant me a cure.) St Gobnait's House and Nearby WellNext to the statue is St Gobnait’s House (also known as St Gobnait’s Kitchen). It is a stone-built, thick-walled, circular hut about 10m in diameter where, according to tradition, St Gobnait lived. It was excavated by M. J. O’Kelly in 1951, revealing evidence for a wooden, rectangular house(/s) beneath the circular structure, as well as numerous iron-smelting and metal-working pits associated with both periods of occupation. Interestingly, Gobnait is the patron saint of ironworkers with her name deriving from ‘gabha’ meaning ‘smith’. There seems to have been little or no interval between the two phases of occupation but only one object, a glass bead, could be said, with all certainty, to have derived from the first period of occupation. Artefacts from later levels were plentiful and included a jet bracelet, a spindle whorl, knives, nails, furnace bottoms, flints, quern stones and whetstones. Following the excavation, limestone columns were erected to mark the positions of the post-holes of the earlier rectangular house. Nowadays, pilgrims, using small stones, carve crosses into the modern limestone columns, in imitation of the crosses carved on older stones at the site. After the pilgrim has said the prayer to St Gobnait at her statue, he proceeds to make a deiseal (clockwise) round of an outer circle which encloses the statue and St Gobnait's House, while reciting seven Paters, seven Aves and seven Glorias. The pilgrim then recites the Credo. The prayers and round are repeated once more for the outer circle. The same is repeated around the inner circle which encloses the house only. At all subsequent stations, the same number of Paters, Aves and Glorias are recited as at this station (i.e. 28 of each). A short distance from St Gobnait’s House, a well was discovered during the excavation. When conservation work was subsequently being undertaken on the site, the well was enlarged, slab-lined and a stone canopy placed over it. It has since been venerated as a holy well. When the pilgrim finishes rounding St Gobnait's House, he drinks from the well. St Gobnait's GraveSt Gobnait’s Grave is located in the graveyard (Reilg Ghobnatan), across the road from St Gobnait’s House. It is a grass-covered mound of loosely packed stones, on top of which are two flat slabs and a piece of a bullaun stone. The slabs are roughly carved with crosses. At its base is a flat slab with two depressions, which is used as a kneeler. Nearby is another piece of a bullaun stone; in the 1950s, O’Kelly recorded two complete bullauns and part of a third. St Gobnait’s Grave is the second station of Turas Ghobnatan and when performing the round, the pilgrim makes two outer circles and two inner circles around the monument, reciting the same prayers as at the first station. Pilgrims have left behind many votive offerings at the grave-site, including rosary beads, pieces of cloth and even mobile phones. St Gobnait's ChurchSt Gobnait’s Church (Teampall Ghobnatan), also located within the graveyard, not far from the 19th-century Church of Ireland church, is a late medieval nave-and-chancel building, that incorporates some features of an earlier Romanesque church, including a lintelled doorway. Although in a ruinous state, the walls are still standing and a lean-to structure was attached to the external face of the north wall in the 1990s to house modern stations of the cross. The church contains 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century burials. The third station of Turas Ghobnatan involves circumambulation of the church. Starting at the west gable, the usual prayers are again recited and these are interspersed with clockwise movement around the church four times, while saying a decade of the rosary on each occasion. The fourth station is inside the church. The pilgrim enters through a doorway in the south wall, faces the altar and recites seven Paters, Aves and Glorias. Once completed, the pilgrim moves to the south window, and placing his hand through the opening makes the sign of the cross on a carved figure on the external wall. The carving in false relief portrays the torso, head and arms of a human figure. It has been interpreted as a sheela-na-gig but does not conform entirely to this type of carving as it does not depict exposed genitalia. Instead, locally, it is considered to be a representation of St Gobnait. Above the chancel arch is the carving of a badly worn human head, with a long neck. This voussoir was probably part of the earlier Romanesque church built on the site. It is known locally as An Gadaidhe Dubh (The Black Robber). There are many folkloric tales regarding this stone, including one which tells of a builder of St Gobnait’s church who stole the saint’s grey horse and the other builders’ tools. He set off with his plunder and rode all through the night, but in the morning, he was found circling the church. Subsequently, his image was carved into the wall of the church as part of his punishment. The Priest's GraveAfter touching the sheela-na-gig, the pilgrim leaves the church and circles it clockwise until he reaches the grave of Fr O’Herlihy, who lived in the 17th century. It is located outside the southeast corner of the church. A relic of the priest was previously wrapped in a cloth and kept in a tin box in the parish; pilgrims used to touch the bone believing it held miraculous powers. A thigh bone of the priest was also previously kept in the parish; pilgrims would kiss it, use it to make the sign of the cross and rub it on ailing parts of the body. On visiting the priest’s grave as part of the pilgrimage, the usual seven Paters, Aves and Glorias are said. The fifth and final station not only includes a visit to the priest’s grave, but also to the bulla and St Gobnait’s Well. The BullaThe bulla is a spherical agate stone. It is lodged in a recess in the west gable of St Gobnait’s Church. The story behind the bulla involves an invader’s attempt to build a castle a short distance from St Gobnait’s church site; on hearing of this, the saint threw the bulla at the castle destroying it. The stone then returned to her hand. When the invader attempted to rebuild his castle, he was again defeated by St Gobnait’s bulla. After this, the stone was often borrowed by people seeking to cure themselves or their animals. On one occasion, it is said that a woman from Macroom borrowed it to cure her cattle, but instead of returning it immediately she kept it for three nights. However, she returned it in a terrified state on the fourth day, after thunderous noises were heard coming from the room where she had placed it. After that, the bulla became, mysteriously, lodged in its present position. Nowadays, the pilgrim stops at the bulla, and makes the sign of the cross on it and three times on himself; a ribbon or a handkerchief is then rubbed on the stone, which is taken home to cure illnesses. As usual, seven Paters, Aves and Glorias are recited. St Gobnait's WellThe final stop of the pilgrimage to St Gobnait is at her holy well, which is a short distance south of the church. Originally, this was accessed via a path leading from the graveyard, but when the Church of Ireland rector’s house was built along this route, access was redirected along the road. On the way to the well, the pilgrim says a decade of the rosary. On arrival at the well, the usual seven Paters, Aves and Glorias are recited and subsequently, the pilgrim takes a drink from the well. The round finishes with the following prayer: ‘Ar impí an Tiarna agus Naomh Ghobnatan mo chuid tinnis d’fhágaint anseo’ (Imploring the Lord and St Gobnait to relieve me of my sickness). If some other form of intercession is required, other than healing, the following is said: A Ghobnait an dúchais (O Gobnait of Ballyvourney, come to me with your help and your assistance.) Many offerings have been left behind at St Gobnait’s holy well and on the nearby tree, such as rosary beads, holy statues and pieces of cloth. It was customary in the past for pilgrims to tear a bit of material from their own clothing and hang it on a sacred bush or tree (a ‘rag tree’) near a holy well. By leaving behind these objects, pilgrims believe they are removing themselves from their illnesses. In cases where someone is seriously ill in Ballyvourney parish, family members and friends will undertake the rounds for twenty-one consecutive days, after which the well is emptied and the pilgrims attend Mass at the parish church in Ballyvourney. It is said that if a trout is seen when the well is emptied, the pilgrims’ prayers will be answered. Medieval Wooden Statue of St Gobnait This wooden statue of St Gobnait probably dates to the late 13th or early 14th century. It is 0.69m high, hollowed out at the back, and the face is worn and featureless except for one eye. Gobnait wears a red dress, blue cloak and white wimple, although most of the paint has now flaked away. There is a tradition that this wooden statue replaced an earlier gold statue of St Gobnait which was buried in a place known as ‘Clais na hIomhaighe’ (‘Pit of the Image’). The O’Herlihys (Muintear Iarlaith) were the traditional ‘airchinnigh’ ('custodians') of St Gobnait’s cult and the keepers of the wooden statue; they lent it to local people who were ill, particularly those with smallpox. In the first half of the 18th century, Protestant John Richardson wrote disparagingly of the peoples’ belief in it, calling it ‘rank idolatory’ and was quick to point out that ‘this Idol hath now lost much of its Reputation, because two of the O Herlihys died lately of small pox’. In c. 1843, it was handed over to the parish priest of Ballyvourney and remains in the parish church but can only be viewed by pilgrims during the annual patterns. In the late 1720s, Richardson spoke of pilgrims kissing the wooden statue and tying handkerchiefs around its neck. An inquiry into the state of Popery in the diocese of Cloyne in 1731 asserted that the statue was set up on the ruins of the old church, where pilgrims encircled it three times on their knees saying Paters, Aves and Credos, concluding with kissing the statue and making an offering of money to it. Smith writing in 1750 stated that the wooden statue was set up on a small stone cross near the west end of the church and that paths around the cross were ‘worn by the knees of the devotees’. He also referred to the custom of tying handkerchiefs around its neck. Daphne Pochin Mould described a similar scenario in the 1950s, stating that ‘one lays the ribbon lengthwise, then around the neck and round the waist, and gives a final rub along the whole statue with it’. Nowadays, pilgrims still use ribbons to “measure” the statue lengthwise and around the waist and feet; these are known as ‘tomhas Ghobnatan’ or ‘Gobnait’s measure’. The ribbons are then taken home, and given to family members and friends to cure illnesses. St Gobnait’s StoneAbout 1km north of Ballyvourney village, in the townland of Killeen, a cross-inscribed stone was discovered near a disused holy well in the 19th century. The two broad faces of the stone are carved with an encircled cross-of-arcs, while on one face is a crudely carved chi-rho. Debased forms of the chi-rho monogram, which is a Greek abbreviation for Christ’s name, occur on stones in Ireland between the 6th and 8th centuries. Above one of the encircled crosses, is a figure in mid-stride, carrying a crozier, with hair parted, giving the appearance that he is walking in a clockwise direction around the circle, no doubt undertaking a deiseal 'round’. His hair resembles a tonsure, akin to that of St Matthew’s in the 7th-century Book of Durrow; this is a good indication that the carving depicts a cleric. The stone is located about 60m from its original location and the antiquarian Windele claimed that many bones were seen when it was removed. Local tradition maintains, that it was here St Gobnait rested when journeying to Ballyvourney. According to this folklore, she had been told by an angel that the place of her resurrection would be where she would find nine white deer grazing. She travelled southward from Inisheer (Aran Island); she saw three white deer at Clondrohid, followed by six at Killeen and finally nine at Gort na Tiobratan where she built her nunnery and remained for the rest of her life. This stone does not form part of St Gobnait’s pilgrimage. Historical Accounts of Veneration to St Gobnait at BallyvourneyPilgrimage to St Gobnait’s church site in Ballyvourney was clearly well established when, in 1601, Pope Clement VIII granted a special indulgence of ‘ten years and quarantines to the faithful who would visit the parish church of Gobnet on her feast-day, would confess and receive holy Communion and would pray for peace among Christian princes, for the expulsion of heresy and for the exaltation of Holy Mother Church’. In order to become indulgenced, Ballyvourney must have already achieved a substantial reputation as a place of pilgrimage, which did not happen instantaneously. In 1603, O’Sullivan Beare and his followers visited the church site and ‘gave vent to unaccustomed prayer and made offerings beseeching the saint for a happy journey’. Geoffrey Keating writing c. 1634 stated that ‘every great tribe had their attendant guardian saint … whom they venerated and honoured’ and declared ‘Gobnuid was for Muscraidhe Mic Diarmada’. Many poems have survived invoking St Gobnait’s assistance and seeking her curative powers. Poet Seán Ó Conaill in his lament 'Tuireamh na hÉireann', written in the mid-17th century, beseeched Gobnait to come to the aid of Ireland to rid the country of the Protestant invader. Sir Richard Cox described Ballyvourney, in 1687, as ‘a small village, considerable only for some holy relick (I think of Gobonett) which does many cures and other miracles, and therefore is a great resort of pilgrims’. Evidently, pilgrimage at Ballyvourney and the cult of St Gobnait was flourishing from at least the 17th century. Ó Murchadha na Ráithneach, in 1722, prayed to Gobnait for a cure for his wife who had smallpox. Later that decade, Richardson described the parish of Ballyvourney as ‘remarkable for the Superstition paid to Gubinet’s image on Gubinet’s day’. Over the centuries, many local poets wrote poetry in honour of St Gobnait and every year, since 1925, a school of poetry, called Dámhscoil Mhúscraí, is held in the village of Ballyvourney. Among the locals, legends concerning St Gobnait are kept alive and still often recited, for example, the journey of Gobnait from Inisheer (Aran Island) to Ballyvourney. The saint is also reputed to have kept Ballyvourney free of the plague, while most accounts speak of recent cures which have been brought about by doing the rounds, drinking water from the holy well, and rubbing Tomhas Ghobnatan to parts of the body which are in pain. Non-religious and secular activities also took place on pattern days at Ballyvourney in modern times. Begging was common and bacachs (beggars) were so numerous at Ballyvourney that they earned the nickname Cléire Gobnaiti (Gobnait’s Clergy). The bacach delivered a peculiar crónán or chant in return for alms. When Mould visited Ballyvourney on St Gobnait’s feastday in 1955, she recorded two beggar women, carrying their infants, sitting on Fr O’Herlihy's grave with arms outstretched for alms. More boisterous activities and faction fighting also occurred at Ballyvourney but these seem to have generally been reserved for the annual Whitsunday pattern, with accounts of fighting between two long-feuding local families, the Twomeys and the Lynchs, taking place on this day. Sources

Archaeological Survey of Ireland: webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/ Harbison, P. 1992. Pilgrimage in Ireland. The monuments and the people. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. Harris, D. 1938. ‘St Gobnet Abbess of Ballyvourney’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquarians Ireland 78, pp. 272-77. Hurley, Fr. 1945-50. ‘Fr Hurley’s Notes’. Unpublished historical and folkloric notes made by PP of Ballyvourney, deposited in Ballyvourney Library. Keating, G. pre-1644. The History of Ireland (Book I and II). Available at: https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100054/index.html Lynch, M. M. 2010. ‘The archaeology and folklore of pilgrimage in Ballyvourney’. Unpublished diploma dissertation in local & regional studies, UCC. MacLeod, C. 1946. ‘Some mediaeval wooden figure sculptures in Ireland: Statues of Irish saints’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquarians Ireland 76, pp. 155-70. Mould, D. P. 1955. Irish Pilgrimage. Dublin: M. H. Gill and Son Ltd. Ní Shuibhne, B. 2010. ‘Naomh Gobnait’. An Sagart, pp. 26-35. Ó hÉaluighthe, D. 1952. ‘St Gobnet of Ballyvourney’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 185, pp. 43-61. O’Kelly, M. J. 1952. ‘St Gobnet’s House, Ballyvourney, Co. Cork’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 185, pp. 18-40. Ó Riain, P. 2011. A Dictionary of Irish Saints. Dublin: Four Courts Press. O’Sullivan Beare, P. pre-1621. Chapters towards the History of Ireland in the Reign of Elizabeth. Available at: https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100060/index.html Plummer, C. (ed.) 1922. Bethada Náem nÉrenn. Oxford. Schools’ Folklore Collection: https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes Smith, C. 1750. The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Cork. Cork: Guy and Co.

4 Comments

Gerard Lynch

2/11/2021 01:54:59 pm

Excellent article.Thank you.

Reply

7/26/2021 09:24:35 am

Thank you for stopping by and reading our articles Gerard.

Reply

Cormac O Sullivan

7/15/2021 07:48:39 am

I visited this site today July 15 /21 with my two daughters. We were greeted by a local lady named hanny who gave us a great education on the site and Saint Gobnait herself which made the visit so much more enjoyable. It felt like this lovely lady was put here by Gobnait herself because we kept meeting her around different areas of the site. The energy of this place felt amazing and healing. My daughter's (both under 6) thoroughly enjoyed their time here and my eldest went on to take her shoes off as if she were on a pilgrimage. I'm very grateful to have this place within driving distance and I'll definitely be back to do the rounds.

Reply

7/16/2021 04:08:21 am

That’s wonderful to hear that you and your family had a great time in Ballyvourney, and meeting the locals certainly adds to the pilgrimage experience.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Herstoric IrelandImmerse yourself in the history of Irish women here! Archives

March 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed